CONFINEMENT

SOPA is an online magazine dedicated to the photographic language. It has two main objectives. The first is to show works that have been in many different and unforeseen ways, inspiring to us, either from emergent or established artists. The second, is that it intends to offer some reflections on contemporary photography in all of its potential.

When we started to discuss what should be the theme or subject to be explored in the first issue of this newly created magazine, confinement came up as one of the most prominent contemporary concepts. We explored the several meanings or appropriations of a word that has become all too familiar during the last year. But even though the establishment of confinement as common sensical is quite recent, due to the coronavirus crisis, confinement has existed literally or metaphorically for as long as human existence. In that sense, it can take different shapes and meanings, and it can also be read or looked at different perspectives. It can be voluntary or compulsory, it can be imposed through modern institutions such as prisons, psychiatric hospitals, detention centres, asylums, retirement homes, through voluntary practices or it can mean one’s own body as is the case of some disabilities, just to name a few.

Artistic works on the theme of confinement have acquired a different pace with the COVID-19 crisis. Our aim was not to avoid nor to diminish the societal relevance of what is currently happening, but rather to show the range of manifestations and the impact of different contexts in its photographic approach.

Works included in SOPA’s first issue revolve around different concepts of confinement, starting with Paul Graham’s in a small apartment in Paris as the consequence of the Terrorist Attacks in November 2015. Entirely photographed inside his home, it is a series with which many can identify in these times, but with substantially different reasons underlying it. It provided us a reflexion on terrorism, illness and isolation that seemed unthinkable ten years ago, whilst making us rethink our everyday objects and routines.

Self-confinement is also a characteristic of Claudia Gori’s The Sentinels, in which the photographer captures the phenomenon of electro-sensitivity in humans, leading them to voluntary isolation and rejecting many of the objects that are constitutive of contemporary life, such as laptops, mobile phones and wi-fi, among many others.

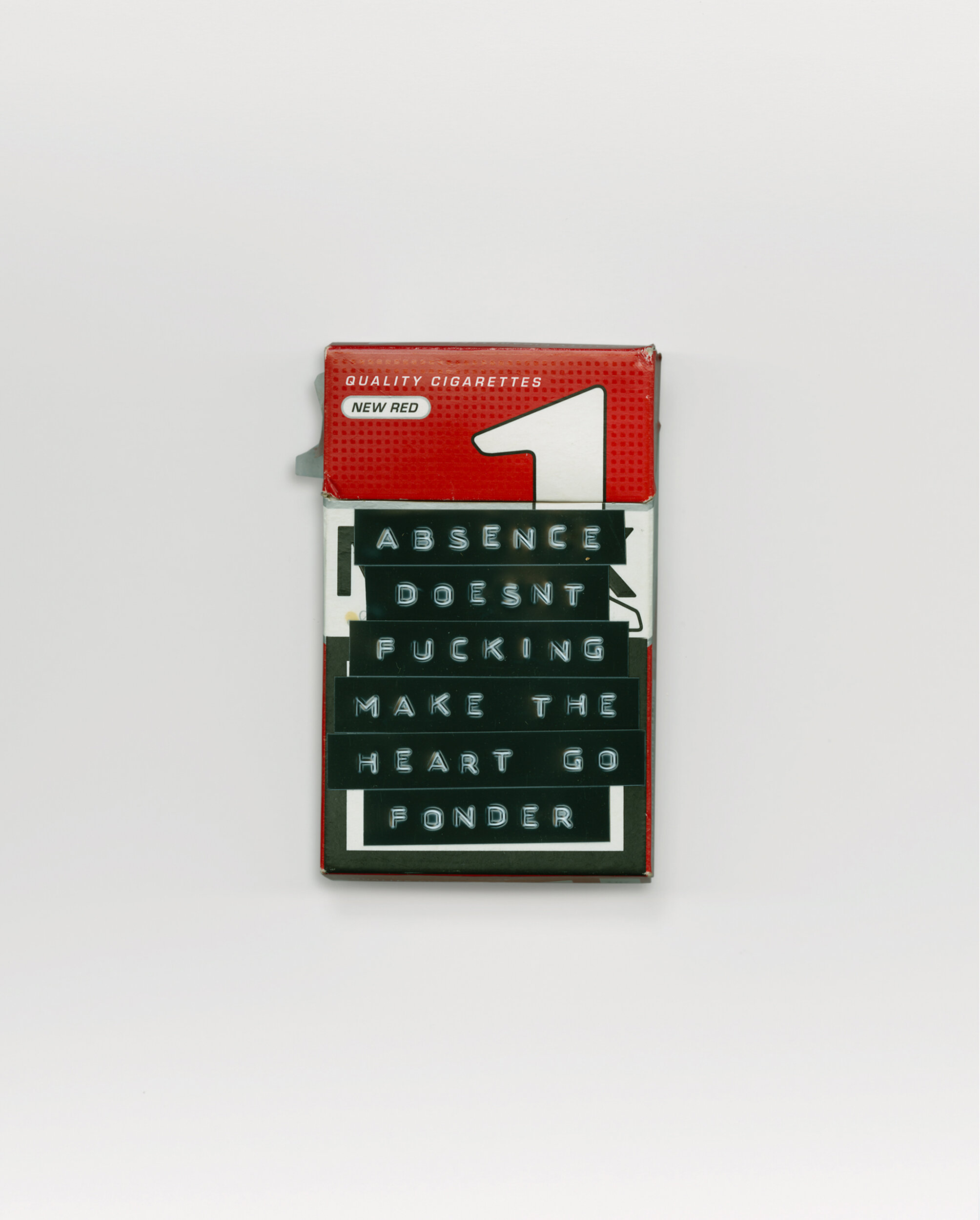

Confinement imposed by others is, of course, also a part of this issue. Either due to law, such as prisons or detention centers, or from other forms, such as political exile, these are examples of how broad this concept is and how “in” and “out” are totally subjective perspectives. Following a collaboration with inmates from the largest privately-run category B prison in the Midlands, United Kingdom, and their families, photographer Edgar Martins produced a body of work that explores the concept of absence from a philosophical perspective. From there on, he inquires on how to deal with something apparently as straightforward as missing someone who is forcefully confined.

Prisons, as an institution, are also generated according to social, cultural and political contexts. On the other side of the Atlantic, Amy Elkins work about long-term incarceration and its psychological effects on individuals. Corresponding for a period of seven years with men who were in solitary confinement and serving life and death sentences, Elkins' work is a powerful statement on the effects of deprivation on the mind when reality is inescapable.

The following work is by Carina Hesper, and involves a different type of confinement, that of visually impaired children living in the Bethel orphanage in Beijing. Again, confinement as a consequence of social and political decisions, more particularly the one-child policy in China and the social and cultural consequences of having a child with disability, leading parents to leave them in orphanages across the country.

To end SOPA’s first issue, and unlike all the previous works, we decided to explore a very different type of confinement, say an inverted one. The work of Daiana Valencia caught our eye for the very basic principle of not being able to get in, rather than wanting to get out. It is a touching work that reflects on political exile due to political persecutions in Argentina following the last military dictatorship in Argentina, between 1976 and 1983.

That being said, we are extremely happy to see the first issue of SOPA put out to the world to see, which we hope it is as exciting for you as it is for us.

Thank you very much,

The SOPA editorial team